A step in the right direction: Billboard-style posters preferred overall at two conferences, but should include more methods and limitations.

Abstract¶

Scientific posters are a frequently used medium of communication at conferences and have grown in popularity over the last decades. However, the design of the traditional poster has largely remained stagnant despite emergence of new relevant research that could have unique implications for how scientific posters are designed for optimal learning. In this study, we examine the impact of a new minimalist, ‘billboard-style’ poster designed to transmit at least one piece of knowledge more efficiently. Attitudinal reactions to new and traditional poster designs were compared in two field studies. We found the billboard-style poster was perceived as easier to learn from, more interactive, and better for promoting scientific discovery. This supports the billboard-style poster design for use in scientific poster sessions. Results also suggested that future improvements to billboard-style designs should aim to efficiently communicate study methods in addition to key findings. Ultimately, these two field studies provide some initial evidence that meaningful improvements in poster effectiveness are possible, and that billboard-style layouts may be a step in the right direction that is worth developing further.

Introduction and Theoretical Background¶

Scientific posters are used widely at conferences across scientific disciplines to disseminate research. Since their inception, poster sessions grew from small events with a few posters in the 1970s into sprawling poster sessions containing hundreds of posters (Hess & Brooks, 1998; Lingard & Haber, 1999; Ilic & Rowe, 2013; Maugh, 1974; Rowe, 2017). Today, posters are the most frequent medium through which scientific knowledge is disseminated at conferences (Rowe, 2017; Rowe & Ilic, 2015). Despite their crucial role in knowledge dissemination, the changing environmental context of posters, and recent evidence questioning their effectiveness, the design of the traditional poster has largely remained stagnant (Rowe & Illic, 2015). This is an especially ripe opportunity for improving knowledge dissemination in science because a wealth of evidence-based theory emerged in recent decades from fields like Instructional Design and Human Factors that is directly relevant to improving the design of scientific posters. Due to their ubiquity, even a small improvement to the knowledge transfer efficiency of the default scientific poster design could increase knowledge dissemination across every field of science.

Previous Research on Scientific Posters¶

Previous research on scientific poster sessions has questioned their effectiveness in facilitating knowledge transfer between poster presenters and session attendees. Several studies have faulted the design and format of the traditional poster as the main impediment to maximizing knowledge transfer with the ever-increasing crowds in poster sessions (Dubois, 1985; Saffran, 1987). Rowe and Illic (2015) especially called for an overhaul of the traditional scientific poster design.

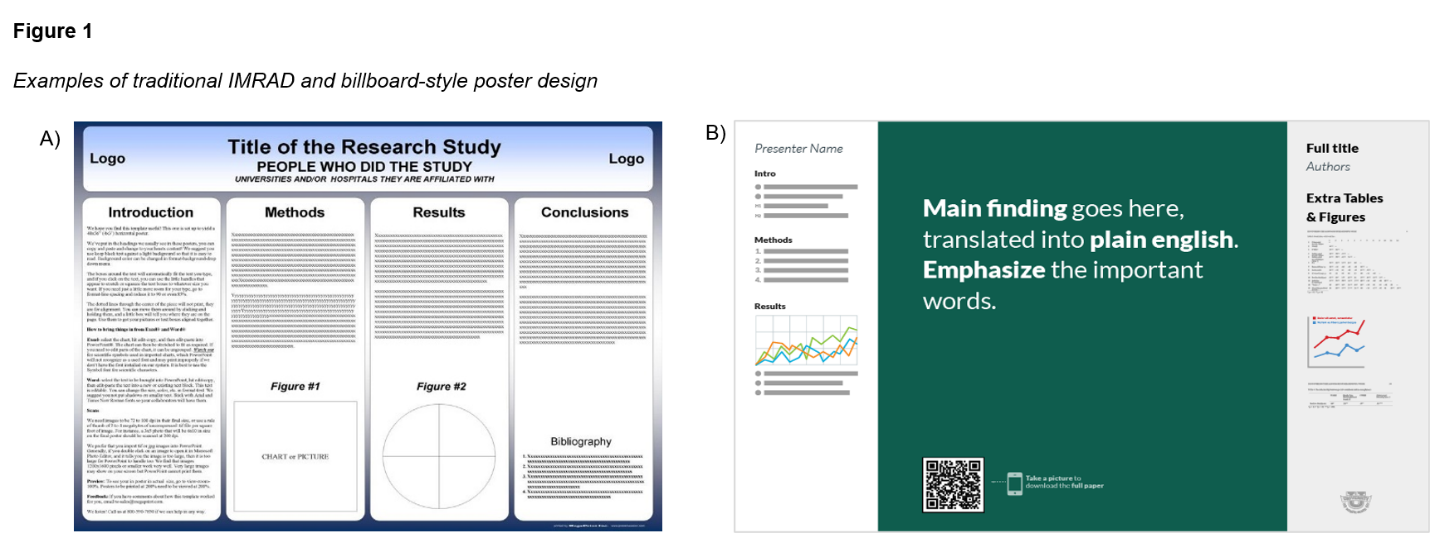

In response to these criticisms of the text-heavy, Introduction-Methods-Results Analysis-Discussion (IMRAD) poster design, a new billboard-style poster (Figure 2,b) was introduced to the scientific community and rapidly gained national attention (Greenfieldboyce, 2019; Morrison, 2019). The features of this billboard-style design were derived from empirically based recommendations from the fields of Instructional Design and Human Factors.

The YouTube video that first introduced this billboard-style poster concept.

Especially influential were Pirolli and Card’s (1999) information foraging theory and Mayer and Moreno’s (2003) work on cognitive load and cognitive overload reduction. In contrast to the traditional poster approach of “hook them with a catchy title, then fill up the rest of the space with as much detail as possible,” the billboard-style poster layout is designed in layers of increasing knowledge transfer and engagement (10 second walk-by learning, 1 minute pause-and-learn, 5 minute stop-and-read, and finally take away more detail to read later), allowing attendees to learn something immediately, and continue learning more the more time they spend with the poster.

First, the billboard-style layout features a large and prominently communicated “main takeaway” that allows attendees to learn something valuable from each poster simply by walking by. This serves to (a) lower the interaction cost of attendees learning from the poster and (b) pre-trains some insight in advance of an attendee stopping to talk to the presenter, in an effort to reduce the cognitive load (Mayer & Moreno, 2003; Pirolli & Card, 1999). Second, information is heavily prioritized in the billboard-style design, with “need to know” information more prominent than “nice to know” information. This is consistent with the recommended "weeding’’ technique where interesting but secondary information is eliminated or de-emphasized to reduce cognitive overload (Mayer & Moreno, 2003). This strategy of strategically presenting information preserves the limited human capacity for processing information and prioritizes the most important information.

Finally, the billboard-style layouts include a mechanism for accessing additional information about the study not presented on the poster. Billboard-style posters typically contain a QR code that attendees can scan with their phone to download full manuscripts and author contact details associated with the poster. This acts as a sweeping repository for less important information, freeing the remaining content on the poster to be more focused.

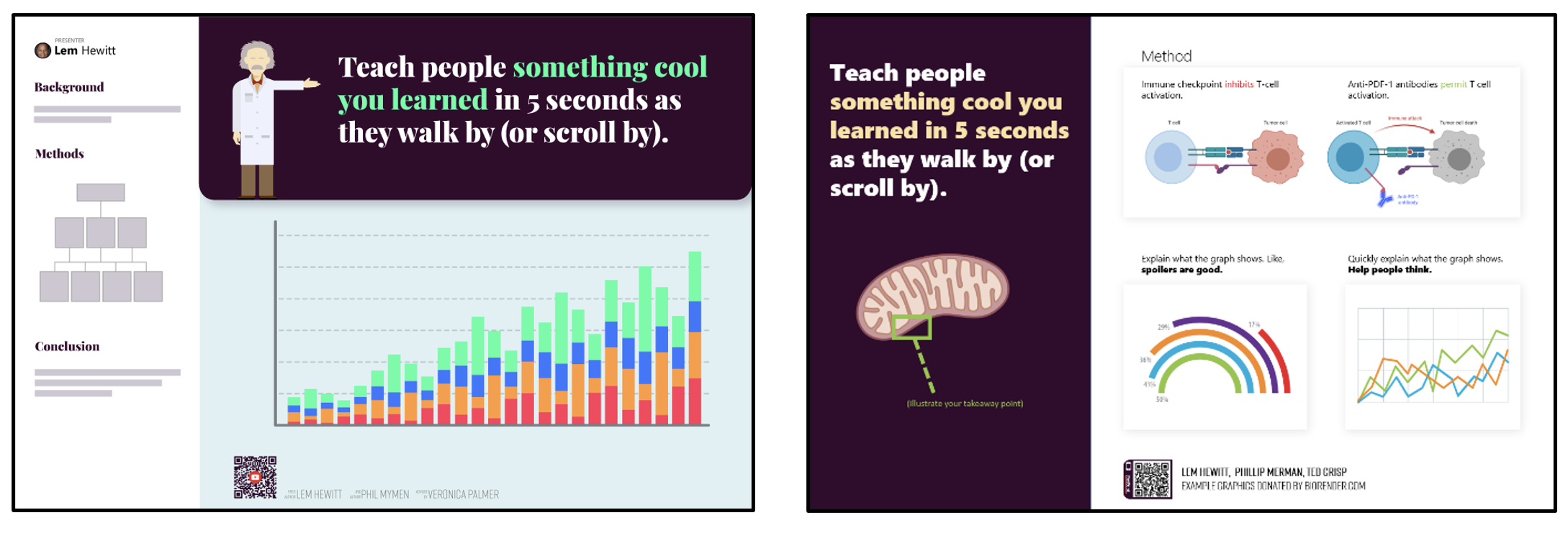

Figure 2:A) An example of a traditional, Introduction, Method, Results, Analysis, and Discussion (IMRAD) poster design. B) A billboard-style poster.

Hypotheses¶

In two studies, we examined the impact of billboard-style poster designs on attendee and presenter attitudes and behaviors.Specifically, we explored how this billboard-style layout, impacted attendee and presenter attitudes towards use of the billboard-style layouts at their current conference and in the future.

Presenter Experience¶

For poster presenters, we were curious to know whether the experience of constructing a billboard-style poster was quantitatively and qualitatively different from constructing a traditional, IMRAD-style poster. A central tenant in the field of User Experience Design is that when something is easier to do, people will do it more (Krug, 2022). For any new poster format to gain wide adoption, the time and effort burden it imposes on those creating the poster is a nontrivial variable. Even if a new approach communicates more effectively, if it requires too much additional effort above the traditional approach, adoption will likely be impeded. The ideal is for a new approach to be both less effort for presenters, and more effective at communicating to attendees, as this may speed adoption.

With both traditional IMRAD and billboard-style, presenters typically start by acquiring templates either from a fellow student (in the case of the traditional poster), or by downloading templates from the Open Science Framework in the case of the billboard-style poster (Morrison, 2019). The layouts differ mainly in terms of the total effort spent placing content on the poster template, and each layout may also have tradeoffs in terms of where time and effort are spent (e.g., aligning content versus re-writing sentences for brevity).

Compared to traditional posters, billboard-style posters are designed to encourage presenters to summarize their study more concisely into concentrated key points and a few key figures. While there may be fewer total words on a billboard-style poster, this lower word limit may force presenters to write more efficiently and economically, which can often be more difficult and time consuming than simply writing (or copy-pasting) effusively.

Compared to billboard-style posters, traditional posters encourage the presenter to ‘fill up all the space’ with text and figures, making the poster appear as dense and rigorous as possible. Although presenters may save time by copy-pasting paragraphs and figures from the essay version of their study summary, ultimately the higher word count of the traditional poster may impose a higher time burden over the billboard-style poster (in terms of time spent placing content). Additionally, the greater quantity of content on a traditional poster may require presenters to spend more time aligning and organizing the extra content.

Although each layout imposes its own effort burden on the presenter constructing it, the billboard-style posters ultimately have less content on them and are designed to be faster to prepare. For this reason, we hypothesized that the billboard-style posters would require less effort (subjectively) and less time to prepare than the traditional poster.

H1a: Billboard style posters will be perceived by presenters as requiring less effort to prepare compared to IMRAD style posters.

H1b: Billboard style posters will take less self-reported time to prepare compared to IMRAD style posters.

Future Behavioral Intentions¶

In psychology, behavioral intentions (i.e., the intention to do something in the future) are formed by a number of factors, including attitudes towards that target (here, posters), the opinions of valued others toward the behavior, and previous habits (Valois et al., 1988). Although these concrete factors each suggest their own research questions as it relates to billboard-style posters, we took an initial step here in measuring these factors by assessing presenters’ overall behavioral intentions toward using billboard-style poster layouts in the future.

We captured presenters’ intentions to use billboard-style layouts after they experienced their performance in-person. If the billboard-style posters are perceived by the presenters as subjectively performing well or better than traditional posters, then it should be likely that they intend to use it again in the future.

H2: Significantly more poster presenters will indicate their intention to use billboard-style posters in future presentations compared to IMRAD style posters.

Attendee Experience¶

As a poster session attendee strolls through the aisles of a poster session, there are a number ways that they may interact with a particular poster. Anything beyond walking past a poster and completely ignoring it (i.e., noticing a poster at all) could be considered as interacting with it. At a minimum, attendees may glance at a poster while mid-walk. As interest increases, they may actively scan something on the poster at a distance, perhaps slowing the pace of their stride. Next, they may pause some distance in front of the poster to take in more. At higher interest, they mean lean-in closer, or separately walk up to the poster to read more.

At the final level of interaction, attendees may engage the presenter in conversation. This conversation may consist of a few concrete questions (e.g., “Did you consider this?”) to supplement the attendee’s reading experience, or may become a deeper, longer conversation (“So, tell me about your poster!”). It may also go ‘off-topic’ as the presenter and attendee get to know each other.

Disengagement too could be meaningful. In Pirolli and Card’s (1999) Information Foraging Theory, ‘patch switching’ — making the decision to leave one information patch (i.e., a poster) to find another — is indicative of the amount of value gained and effort invested in the original patch by the forager (here, the attendee). Time spent, learning gained, and subjective reactions at each of the above gradations of engagement with a poster are all theoretically meaningful.

We mention all of these potential measurement points to illustrate that there is a great deal of research yet to be done on scientific posters, and also to situate the narrow scope of the questions we investigated in these studies. Here, we focused on whether the billboard-style posters differed from traditional, IMRAD-style posters qualitatively in terms of their perceived interactivity.

Perceived interaction cost¶

Billboard-style posters are designed to have a lower interaction cost for attendees than traditional posters. That is, they are designed to be less effort for attendees to learn from than traditional posters. As discussed previously, achieving a lower interaction cost results in a number of positive outcomes, especially in terms of increased user engagement (Lam, 2008). As an initial test of the billboard-style poster’s interaction cost, we assessed whether attendees subjectively perceived billboard posters as being more interactive. To complement this, we also assessed whether presenters perceived their billboard-style posters as receiving a higher number of interactions from attendees versus the IMRAD posters they’d presented.

H 3a : Billboard-style posters will be perceived as significantly easier to interact with by attendees.

H3b: Billboard-style posters will be perceived by presenters as receiving a higher number of interactions from attendees.

Aesthetic usability¶

Visual appeal, or aesthetic usability, is the general, quickly-formed sense of attractiveness that a particular design conveys to its users (Grishin, 2018). A number of subtle design factors contribute to aesthetic usability, including spacing, alignment, color harmony, and rhythm (a simple example of rhythm is having a consistent line height for text). In terms of user engagement, aesthetic usability is a factor in the perceived interaction cost of a design, with higher aesthetic usability resulting in a sense of lower interaction cost and thus a greater likelihood of engaging with a particular design (Grishin, 2018). The billboard-style posters are designed to be less cluttered than traditional posters, or at least to contain visual clutter to secondary areas, so that the majority of space on the poster is dedicated to large, clear and easy-to-read text and figures. A lack of visual clutter is thought to be one factor in perceived usability (Lam, 2008). Thus, we expect that the less cluttered billboard-style posters will be perceived as more aesthetically usable (phrased as ‘visually appealing’) by attendees.

H4: Billboard style posters are perceived as more visually appealing than IMRAD style posters.

Learning outcomes¶

A key goal of any poster session is for attendees to learn about new research in their field. The learning that takes place in a poster session likely takes many different forms, from detecting patterns and trends in the field overall from all the posters, down to learning about a single component of a single study or gaining professional skill development from off-topic discussions with presenters. For a single poster, the attendee may learn from the poster itself (reading a figure or takeaway), from the presenter apart from the poster (e.g., from listening to an elevator pitch), or from a poster-presenter interaction (e.g., when a presenter explains a figure). As an initial step towards assessing the effect of the poster itself on attendee learning outcomes, we assessed whether attendees felt the billboard-style layouts improved their own overall learning experience in the poster session.

H5: Billboard style posters are perceived as improving learning from poster sessions compared to IMRAD style posters.

If the goal of an individual poster is to communicate information about a single scientific study, then what is the goal of the poster session overall? Here, there may be multiple goals. Scientists may benefit from networking with other researchers and building deeper transactive memory about who is studying what (Brandon, 2004). The wide focus of a poster session may also promote serendipitous learning of stumbling across unexpected insight outside an attendees normal research area (Lane et al., 2021). Ultimately, all of these goals may serve the superordinate goal of promoting scientific discovery. To begin assessing the impact of poster design on such session-wide goals, we tested whether this billboard-style was perceived as facilitating overall scientific discovery compared to traditional IMRAD posters.

H6: The billboard-style layout will be perceived as promoting scientific discovery more than the traditional IMRAD design.

Attendee-Presenter Interactions¶

When an attendee chooses to stop and talk to a poster presenter, the features of the poster design may have an effect on the nature and quality of that conversation. These effects can be divided into two categories: The amount of information conveyed from the poster to the attendee prior to stopping, and the amount of information transmitted from the poster itself to the attendee while they converse with the presenter. This first version of the billboard-style poster was designed especially to communicate more information about the study as the attendee walks by, prior to stopping. Namely, this billboard layout was designed to transmit the main takeaway of the study prior to stopping, in contrast to the traditional poster which communicates only the general subject through the title (Morrison, 2019).

H7: Billboard style posters are more effective at communicating the main takeaway of the study compared to IMRAD style posters.

Morrison (2020) suggested that successfully teaching attendees more about the study before they stop to talk could increase the amount of what Mayer and Moreno (2003) refer to as ‘pre-training’, where a learner learns some details about a concept in advance, prior to a more intensive training session (typically a class, but here this could be talking to the presenter). Pre-training has been shown to reduce the cognitive load of subsequent learning sessions and to ultimately improve learning outcomes (Mayer & Moreno, 2003).

There are many ways that this additional pre-training could affect the presenter-attendee conversation itself (e.g., which topics are discussed, the depth of questions are asked, the degree to which the conversation wanders off-poster). In the broader scope of our initial studies here, we sought to detect whether there was a perceived change in the quality of the conversation at all between billboard and traditional-style posters.

H8: Billboard style posters will be perceived by presenters as creating a higher quality of interaction with attendees.

Overview of studies¶

In two field studies, we sought to understand how billboard-style and traditional poster designs were evaluated among those presenting posters and those attending poster sessions. In our first study, we tested the effect of a ‘full rollout’, where every poster was designed using a billboard-style layout (Figure 2, B). In our second study, we tested the effects of a heterogeneous session, where half the posters in the session were traditional IMRAD (Figure 2, B) poster designs and half used a billboard-style layout.

Methods¶

Study 1: Full rollout where all posters were billboard-style¶

In an initial exploration of poster design, we partnered with the International Health Economics Association (iHEA) Immunization Economics Special Interest Group to examine attendee and presenter reactions to billboard-style poster designs. The Immunization Economics pre-conference (2019) was attended by 126 participants from 73 institutions across 31 countries; but all posters were displayed in a central location accessible to all iHEA conference participants. All poster presenters were emailed a billboard-style poster template to use while preparing their posters. The poster session featured 41 poster presentations, all with a billboard-style layout.

Materials and Administration¶

Poster session attendees and presenters were surveyed at the conclusion of the session (62 attendees, 59 respondents, response rate 95.16%). All poster presenters (n = 26) were asked to indicate which poster (alternative poster, traditional poster, no preference) they believed took less time to prepare, led to more interaction with participants, and which they were more likely to use for their next presentation. All attendees (including presenters; n = 59) were asked to indicate their preferred poster layout (alternative poster, traditional poster, no preference) across the following dimensions: learning experience, visual appeal, approachability, and supporting scientific discovery. Finally, participants were asked a series of open-ended questions addressing the strengths, room for improvement, and general comments about the billboard-style poster template.

Analysis¶

For the preference questions, a series of χ2 goodness of fit tests were conducted to determine if poster presenters and attendees preferred the alternative poster design over the traditional poster design or had no preference.Specifically, we compared the observed preferences for poster design to the expected preferences for poster design. For the expected preferences, we assumed an equal distribution of preferences across all three response options (e.g., 1/3 of participants preferred the alternative poster design, 1/3 of participants preferred the traditional poster design, and 1/3 of participants indicated no preference for traditional or alternative poster design). To account for the multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was applied with a significance cutoff value of alpha = .0056.

The open-ended survey responses were analyzed using conventional content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). First, the qualitative responses were broken down into individual recording units containing an evaluation (positive, negative, or neutral) and an object (target of evaluation), resulting in n = 144 units. Second, a codebook was developed using the constant comparative method shown in Supplemental Table 1 (Glaser, 1965). Third, two authors independently coded the qualitative responses, resulting in moderate interrater reliability (pooled kappa = .74; De Vries et al., 2008). Finally, any remaining discrepancies in the qualitative responses were discussed until full agreement was reached.

During codebook development, three overarching categories of qualitative response were identified: poster features, poster experience, and irrelevant information. The poster features category refers to evaluations of specific design features and design choices on the different posters (e.g., QR code, font, large central block for key message, etc.). The poster experience category refers to participants’ overall reactions and evaluations towards billboard-style posters (e.g., what they felt, thought, etc.). The irrelevant information category was used to filter out non-evaluative or unrelated responses. By organizing qualitative responses in this manner, we can separate overall evaluations of the billboard-style poster from specific design-related feedback.

Study 2: Mixed session with half billboard-style, half traditional¶

In study 2, we examined attendee and presenter reactions at a poster session where half the posters were traditional, IMRAD-style posters, and half were billboard-style posters. The poster session was hosted by The United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC)'s Office of Laboratory Science and Safety (OLSS) during the CDC’s 2020 Laboratory Science Symposium (LSS). LSS is an internal, annual event for CDC’s laboratory scientists to showcase their work across the agency. Presenters were allowed to choose between using the billboard-style template or the traditional template for their poster presentations. Of the 68 posters that were presented, 33 (48.5%) were designed using the billboard-style poster format.

Materials and Administration¶

The CDC’s Office of the Associate Director for Communications’ (OADC) Graphic Services Scientific Poster Team (SPT) worked with multilevel groups including CDC scientists and web teams to develop a CDC billboard-style template to intentionally address the needs of the agency. The Design Council’s “Double Diamond Design Process” was used to support the design strategy of the billboard-style poster template (Ball, 2019). This template was further reviewed by OADC’s Quality Assessment Quality Control Office and underwent usability testing to ensure quality and design standards were met.

Survey Instrument¶

A survey was administered during the poster session to n=95 respondents, representing 40% of people who attended or presented at the poster session. All participants indicated which poster design they were likely to use in their next presentation (new poster, traditional poster, or no preference).

Presenters. Poster presenters rated their confidence that the details of their work were conveyed to poster attendees (e.g., “Do you feel confident that the details of your work were well conveyed to poster attendees?”) by indicating “Yes”, “No”, or “Maybe.” Presenters also indicated their subjective level of interaction with poster attendees (e.g., “How do you rate your level of interaction with poster attendees?”). Finally, to address Hypothesis 1b, poster presenters also self-reported how many hours it took to prepare their poster (e.g., “Approximately how many hours did it take to prepare the poster?”). The number of reported hours was an open-ended approximation.

Attendees. Poster session attendees self-reported which poster design they preferred (billboard-style poster, traditional IMRAD poster, or no preference) along the following dimensions: visual appearance, understanding the details and rigor of the study, ease of understanding the main message, and productive discussion with the presenter. Finally, attendees’ ratings of levels of poster interactivity were captured using a Likert-type scale (1 = least interactive, 5 = most interactive).

Analysis¶

A series of tests were conducted to examine the impact of poster design on participants’ attitudes, preferences and behavior. Categorical response questions (e.g., Which poster do you prefer: traditional, alternative, or same) were analyzed using χ2 goodness of fit tests to determine if reported preferences were different from expected preferences. For the expected preferences, we assumed an equal distribution of preferences across all three response options (e.g., 1/3 of participants preferred the billboard-style poster design, 1/3 of participants preferred the traditional IMRAD poster design, and 1/3 of participants indicated no preference for traditional or billboard-style poster design).

Likert-type responses (e.g., levels of interaction with poster attendees, 1 = least interactive, 5 = most interactive) were analyzed using independent sample t-tests. Self-report responses of time spent preparing a poster were compared using a Mann-Whitley U-test to account for the floor effects in the time data. Poster preferences by demographic levels (e.g., presenter vs. attendee status and career level) were analyzed using chi-squared tests of independence. To account for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was applied to maintain a familywise error rate of alpha= .05. Bonferroni corrected cutoff values are denoted, where appropriate, within the results.

Results¶

Overall, attendees preferred billboard-style poster layout over the traditional IMRAD layout for learning, ease of interaction, and ultimately facilitating scientific discovery. Presenters perceived the billboard-style layout as being easier (but not faster) to prepare, more interactive to attendees, and in both studies voiced a desire to use the billboard-style poster layout over IMRAD in future conferences. However, participants in both studies felt that future improvements to the billboard-style layout should focus on communicating study methods and rigor more prominently, in addition to the key takeaway. A summary of results and hypotheses can be found in Table 1.

Study 1: Perceptions of poster design at all-billboard-style session¶

Of the 62 attendees present at the full-rollout session (where every poster was billboard-style), 59 completed a paper survey (response rate of 95.16%). Twenty-six participants were poster presenters and most (22) had experience preparing and presenting a poster presentation in the past. The remaining 33 participants were attendees of the poster session. Of the 59 subjects, almost all (56, 94.92%) had experience attending a poster presentation in the past.

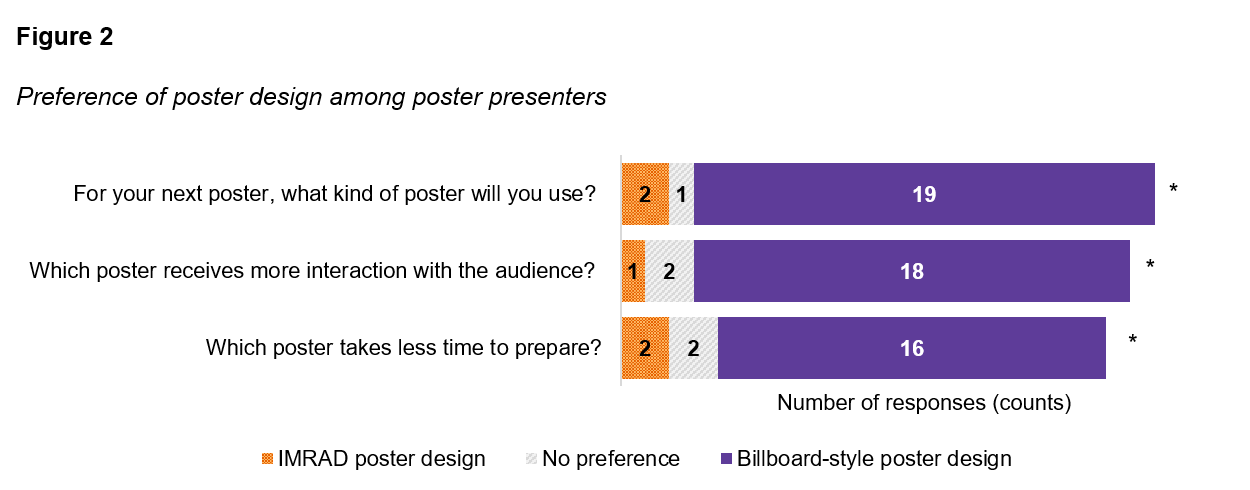

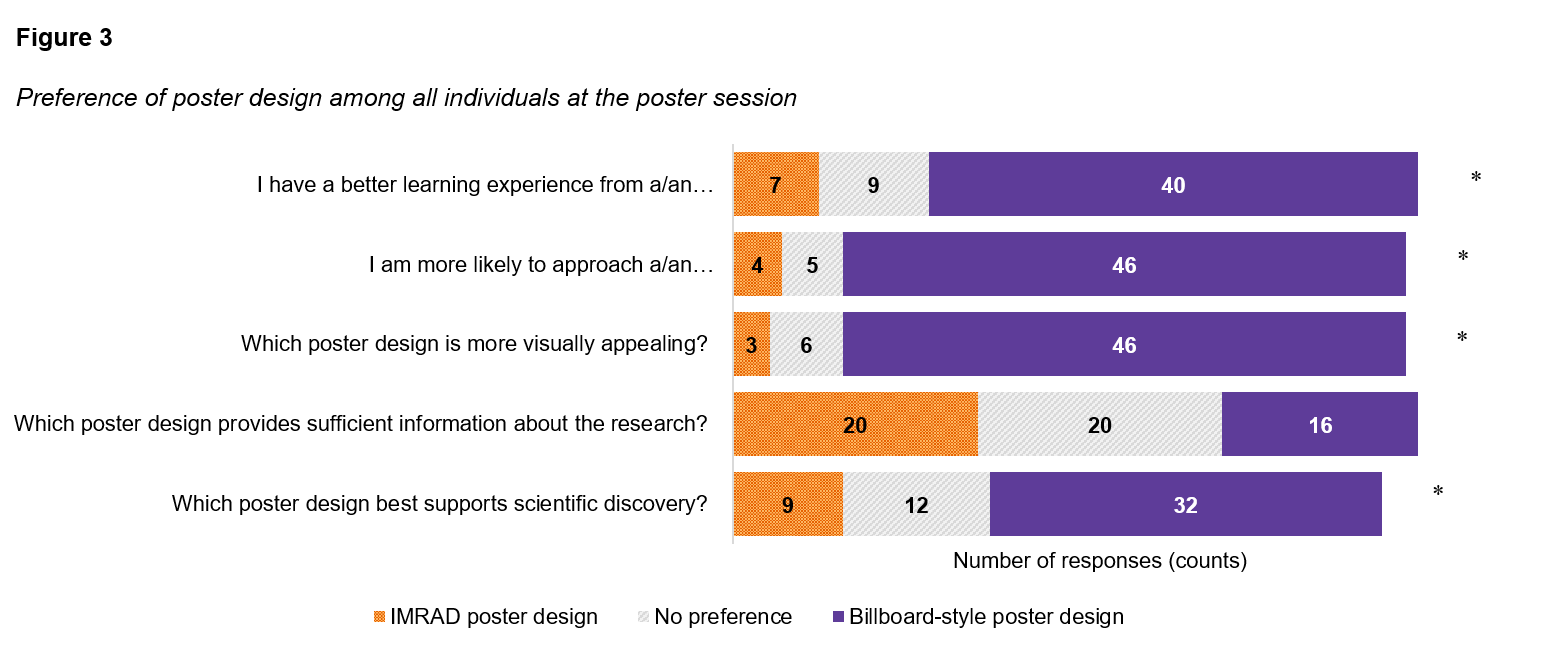

Compared to the expected preference distribution, poster presenters (N = 26) indicated that the billboard-style poster takes less time to prepare (supporting Hypothesis 1a), chi-squared (2, N = 26) = 19.60, p < .001, receives more interaction from the audience, chi-squared (2, N = 26) = 26.00, p < .001 (H3b, supported), and are more likely to continue using the billboard-style poster for their next presentation, chi-squared (2, N = 26) = 27.91, p < .001 (Figure 3, supporting Hypothesis 2. Similarly, compared to the expected preference distribution, the full sample of people who attended the poster session (N = 59) rated the billboard-style poster as more visually appealing, chi-squared (2, N = 59) = 62.87, p < .001 (H4, supported), and more approachable, chi-squared (2, N = 59) = 62.66, p < .001 (H5, supported). Attendees showed no significant preference as to whether billboard-style or traditional posters provide sufficient study information (2, N = 59) = .57, p = .75. Billboard-style posters were preferred by attendees for providing a better learning experience chi-squared (2, N = 59) = 36.68, p < .001, and promoting scientific discovery chi-squared (2, N = 59) = 17.70, p < .001 (see Figure 4, supporting Hypotheses 5 and 6.

Figure 3:Preference of poster design among poster presenters

Poster presenters indicated their preference of poster design (N=26). A significant number of presenters preferred the billboard-style poster for all three questions. * Indicates significant at the Bonferroni corrected p<.0056 level.

Figure 4:Preference of poster design among all individuals at the poster session

All respondents indicated their preference of poster design (N=59). A significant number of respondents preferred the billboard-style poster for four of five questions. * Indicates significant at the Bonferroni corrected p<.0056 level.

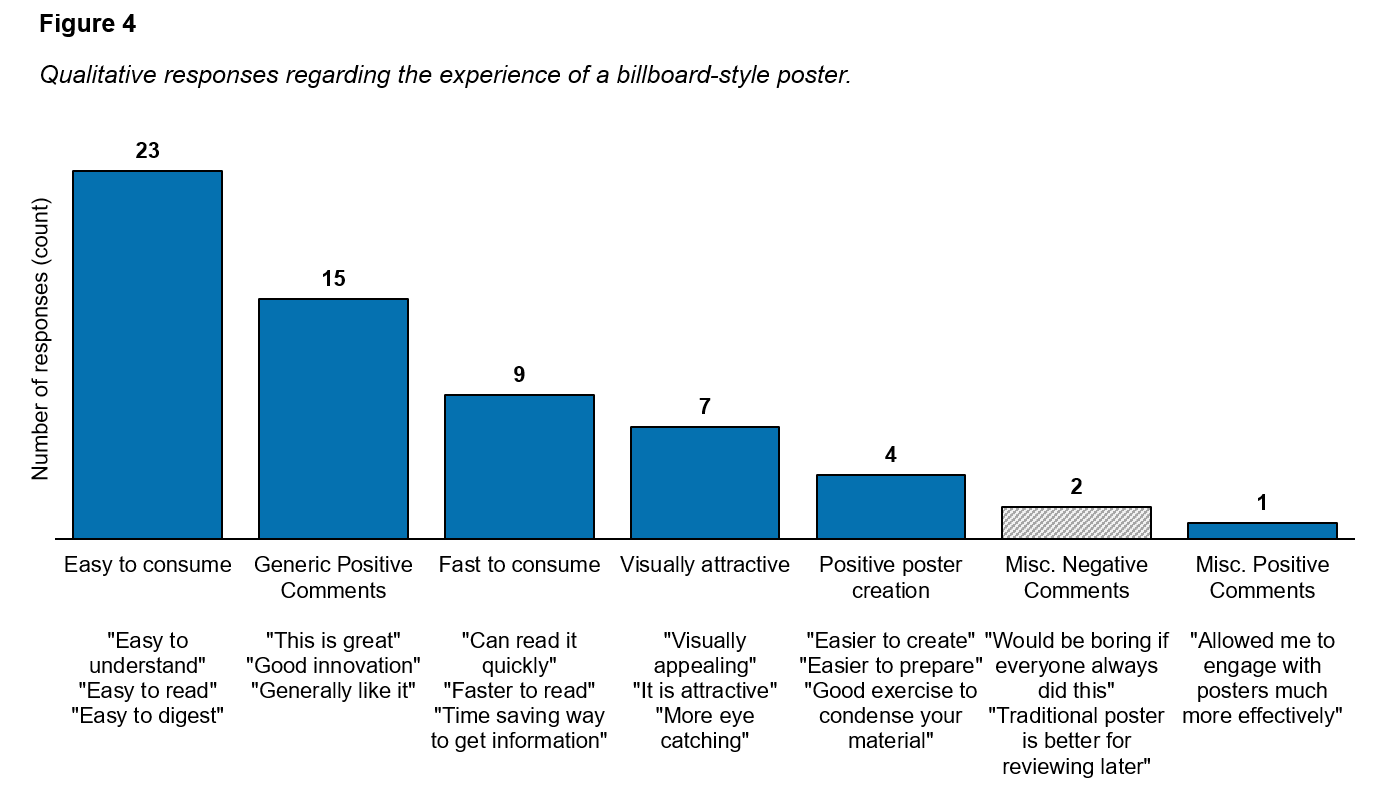

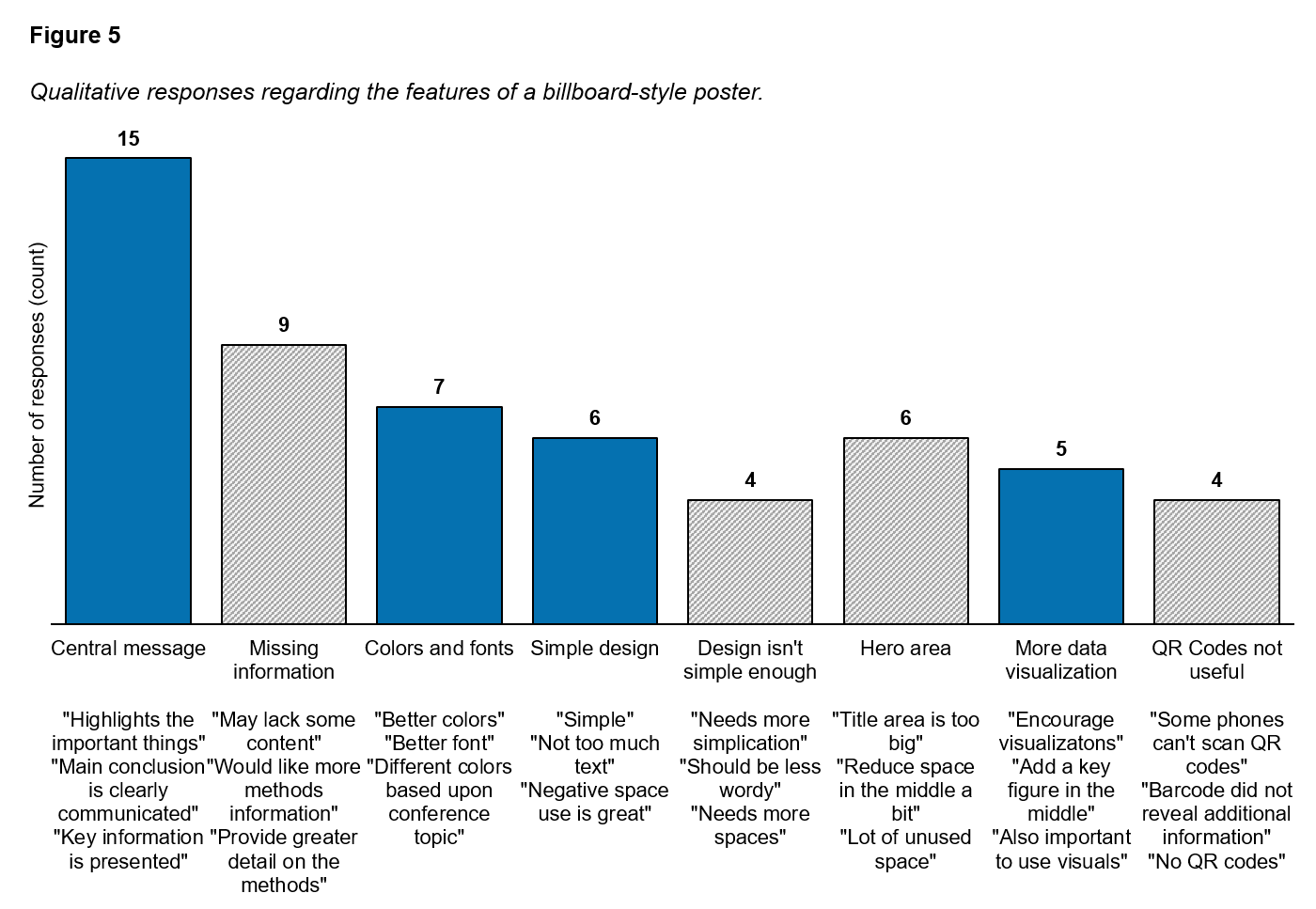

The qualitative responses mirrored the quantitative results. Within the poster experience category (n = 61 response units), participants indicated that the billboard-style poster was easier to consume, faster to process, and visually more attractive (Figure 5). For poster features (n = 66 response units), respondents indicated an overall preference for the “key takeaways,” but also indicated a preference for more information and more visualizations (Figure 6). These findings complement the quantitative results; the billboard-style poster was perceived as better for communicating scientific findings but had mixed opinions for providing sufficient information about the research. The remaining qualitative results were largely inconsistent or idiosyncratic, suggesting that these findings may represent individuals’ personal preferences instead of reliable evaluations of the billboard-style design (e.g., participants indicating approval or disapproval for the QR code).

Figure 5:Qualitative responses regarding the experience of a billboard-style poster. Blue bars indicate comments that support a positive regard for the billboard-style poster, with grey bars indicating negative comments.

Figure 6:Qualitative responses regarding the features of a billboard-style poster. Blue bars indicate comments that support a positive regard for the billboard-style poster, with grey bars indicating negative comments.

Study 2: Perceptions of poster design at mixed session (with both traditional and billboard-style posters)¶

Of the 95 respondents surveyed at the mixed poster session (part traditional, part billboard-style), 62 respondents (65.26%) were poster presenters, and 33 respondents (34.74%) were poster session attendees. To be eligible to take the survey, poster session attendees must have viewed a minimum of 8 posters with at least 3 of those posters being the new billboard-style design. The majority of respondents for poster presenters and poster attendees were Subject Matter Experts (SMEs; 43.16% and 18.95%, respectively). Also represented were entry-level staff (18.94% presented, 9.47% attended) and CDC leadership (3.16% presented, 6.32% attended).

First, poster presenters reported how much time it took to prepare their respective posters. Due to the skewness of responses, a Mann-Whitney U-test was conducted to determine if there was a significant difference in the time spent preparing traditional vs. billboard-style posters. Results indicated no significant difference, z = 0.92, p = .36, suggesting that the billboard-style poster (Med = 5.0 hours) did not take significantly less time to prepare than a traditional poster (Med = 6.0 hours), indicating that Hypothesis 1b was not supported.

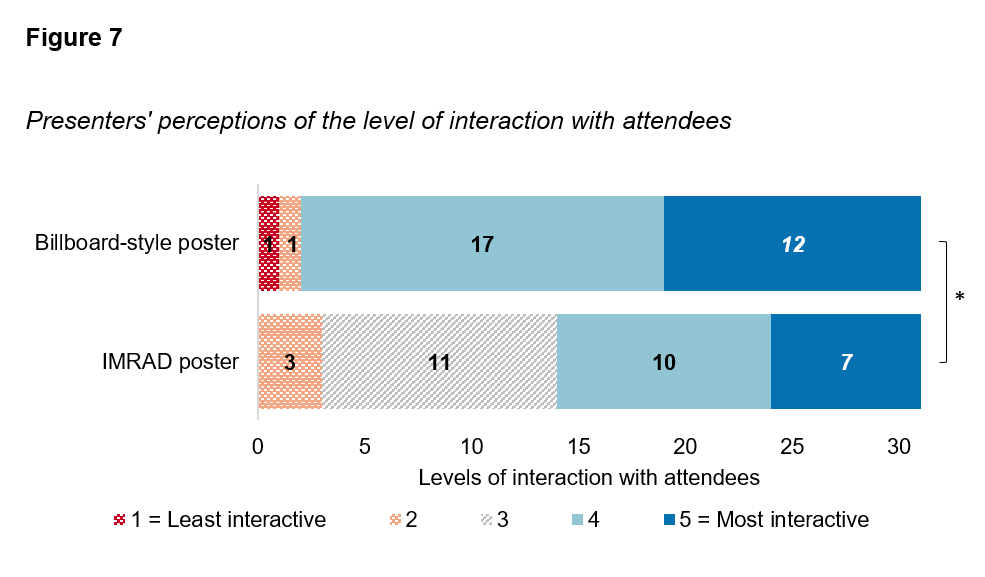

Presenters then indicated their confidence in communicating the contents of their poster and their levels of interaction with session attendees. To evaluate the influence of poster design on confidence in communication, a chi-squaredtest of independence was conducted. Results indicated a non-significant effect, chi-squared(2, N= 62) = 3.09, p = .21, suggesting that presenters’ poster design does not influence their confidence in communicating their study to others. An independent sample t-test was conducted to determine if poster design influenced perceived levels of interaction with session attendees (Figure 7). A significant difference was found, t (60) = -2.06, p = .04, indicating that the billboard-style poster design is perceived as being more interactive (M = 4.19, SD = 0.87) than the traditional poster design (M = 3.71, SD = 0.97).

Presenters’ perceptions of the level of interaction with attendees

Figure 7:Qualitative responses regarding the features of a billboard-style poster. Blue bars indicate comments that support a positive regard for the billboard-style poster, with grey bars indicating negative comments.

A) Poster presenters indicated their perceived level of interaction with attendees (N=62). B) Comparing weighted averages showed that billboard style poster presenters perceived a significantly higher level of interaction with attendees over IMRAD poster presenters. Standard error bars are indicated around the mean response. * Indicates significance at the p < .05 level

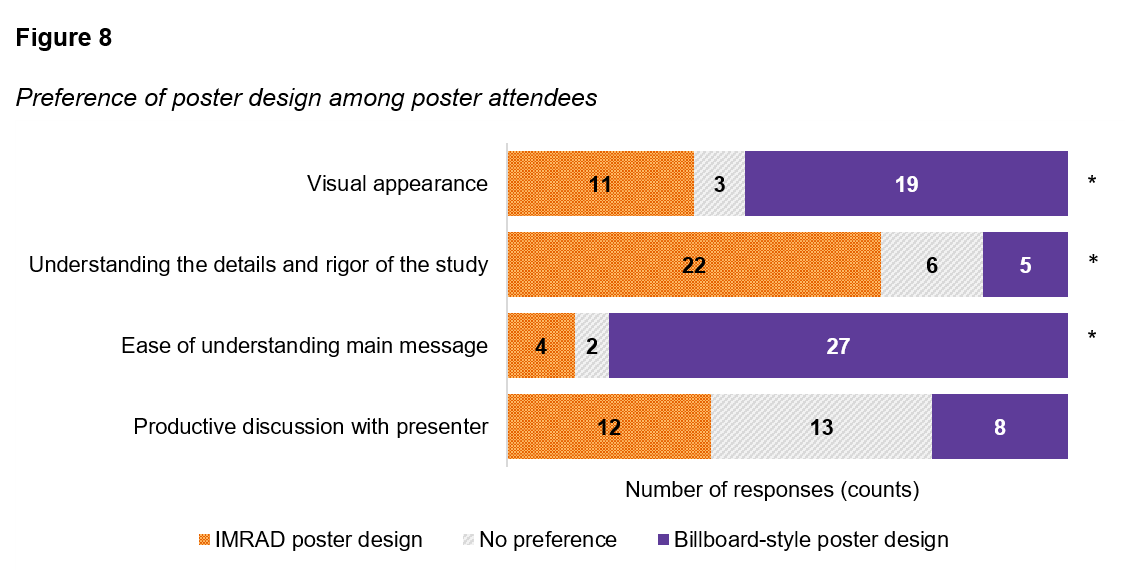

Poster session attendees were asked to indicate their preference (e.g., new poster, traditional poster, or no preference) along the following dimensions: visual appearance, understanding details and rigor of the study, ease of understanding the main message, and productive discussion with presenters. To account for the multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was again applied, with a significance cutoff value of alpha = .0125.

Poster attendees observed preferences were significantly different from expected preferences for the following dimensions: visual appearance, chi-squared (2, N = 33) = 11.64, p = .003; ease of understanding the main message, chi-squared (2, N = 33) = 35.09, p < .001; and communicating the details and rigor of the study, chi-squared (2, N = 33) = 16.55, p < .001. The billboard-style poster was preferred for visual appearance (58%), supporting Hypothesis 4. Observed preferences were not significantly different from expected preferences for perceptions of productive discussion with presenters, chi-squared(2, N = 33) = 1.27, p = .53, failing to support Hypothesis 8. Finally, billboard style posters were preferred for and understanding the main message of the poster (82%), supporting Hypothesis 7, while the traditional IMRAD poster was preferred for communicating details and rigor of the study (67%, see Figure 8.

Figure 8:Preference of poster design among poster attendees. A significant number of attendees preferred this Billboard-style poster design for visual appearance and ease of understanding the main message but preferred the IMRAD poster design for understanding the details of the study (N=33). * Indicates significance at the Bonferroni corrected p < .0125 level.

Next, participants were asked to indicate which poster design they intended to use for their next poster presentation. A chi-squaredgoodness of fit test was again used to compare observed preferences to expected preferences (1/3 billboard-style poster, 1/3 traditional IMRAD poster, and 1/3 no preference). The majority of poster presenters (66%) indicated that they intended to use the billboard-style poster design at their next presentation. Additionally, career level was not found to influence poster preference (chi-squared[2, N= 95] = 2.28, p = .319).

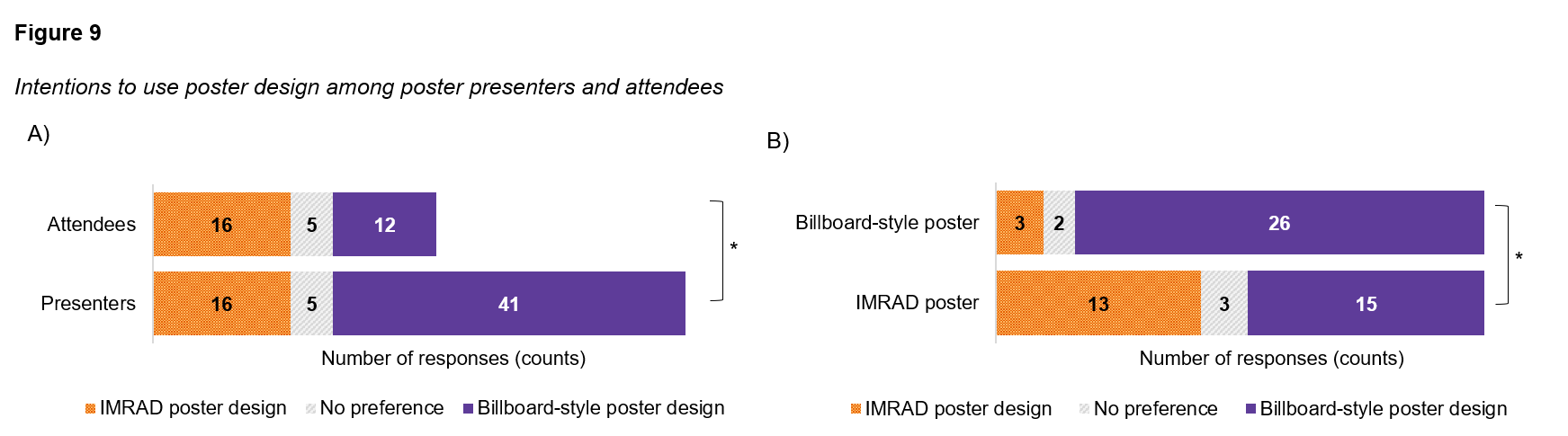

Figure 9:Intentions to use poster design among poster presenters and attendees. A) A significant number of poster presenters would prefer to utilize the billboard-style poster design for their next presentation compared to attendees (N=95). B) Significantly more presenters using the billboard-style poster for this event wanted to use it again for their next meeting compared to those using the IMRAD format (N=62). * Indicates significance at the Bonferroni corrected p < .025 level.

Among poster presenters, a subsequent chi-squaredtest of independence was used to examine the influence of presented poster design at the CDC LSS conference on the intention to use a certain poster design at the next presentation. A significant effect of presented poster design was found, chi-squared(1, N= 62) = 9.19, p = 0.002). Presenters who used the billboard-style poster format at the CDC LSS conference reported a higher intention to use the billboard-style format at their next presentation (84%) than those who used the traditional design (48%), supporting Hypothesis 2 (see Figure 9).

Table 1: Summary of Hypotheses¶

| Hypothesis | Description | Supported | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presenter Experience | |||

| H1a | Billboard style posters will be perceived by presenters as requiring less effort to prepare compared to IMRAD style posters. | ✔ | 1 |

| H1b | Billboard style posters will take less self-reported time to prepare compared to IMRAD style posters. | 🗶 (n.s.d) | 2 |

| H2 | Significantly more poster presenters will indicate their intention to use billboard-style posters in future presentations compared to IMRAD style posters. | ✔ | 2 |

| Attendee experience | |||

| H3a | Billboard-style posters will be perceived as significantly easier to interact with by attendees. | ✔ | 2 |

| H3b | Billboard-style posters will be perceived by presenters as receiving a higher number of interactions from attendees. | ✔ | 2 |

| H4 | Billboard style posters are perceived as more visually appealing than IMRAD style posters. | ✔✔ | 1&2 |

| H5 | Billboard style posters are perceived as improving learning from posters sessions compared to IMRAD style posters. | ✔ | 1 |

| H6 | The billboard-style layout will be perceived as promoting scientific discovery more than the traditional IMRAD design. | ✔ | 1 |

| Attendee-presenter interactions | |||

| H7 | Billboard style posters are more effective at communicating the main takeaway of the study compared to IMRAD style posters. | ✔ | 2 |

| H8 | Billboard style posters will be perceived by presenters as creating a higher quality of interaction with attendees. | 🗶 (n.s.d) | 2 |

Discussion¶

The ubiquity of posters in science carries a profound opportunity to improve scientific communication. Given how many posters are presented every year, a small improvement to the poster’s ability to transmit knowledge could accelerate learning across science. The results of the above studies suggest that such improvements are possible and should be pursued further. The ‘billboard-style’ approach to posters is new and still evolving, with many new layouts introduced even since our data was collected (see Morrison, 2020). However, even the simple “minimalist” billboard-style design tested here may have taken a small step towards more effective poster sessions, albeit with some tradeoffs observed with this particular layout. This early billboard-style layout seems to be, as one attendee commented, an imperfect “step in the right direction.”

Across both studies, the billboard-style design was perceived as more interactive, and as making it easier to learn at least the main takeaway from every poster in the room. Participants in the all-billboard-style session, especially, felt that the billboard-style posters aided their own learning and promoted discovery in science over the traditional design. The goal of this ‘version 1’ billboard layout was to efficiently communicate the main finding of the study to all attendees, and both our studies seemed to confirm that it succeeded in that aim. However, for billboard posters to fully overtake the traditional design in all areas (at least in terms of attendee perceptions) more work likely needs to be done to make them communicate study data and methods effectively as well. Recently released “generation 2” billboard-style layouts (see Morrison, 2020) seek to do exactly this and make methods and data considerably more prominent than on the Morrison, 2019 layout, however these new layouts have yet to be tested.

Ultimately, these studies represent some encouraging initial reactions to an early attempt at creating a more theory-grounded poster format. With continued improvements to poster designs, and to the methods used to test poster effectiveness, science can move towards a future where scientific posters transmit knowledge more efficiently to all attendees, and where that increased transmission can be measured effectively.

Limitations¶

The major limitation of both these studies is that they rely primarily on self-reported, subjective perceptions. It sounds auspicious that in two separate studies, people seem to prefer this particular new poster design over the old approach and perceive it as functioning more effectively (mostly). But as is often said in both psychology and user experience design: what people say may be different from what they do. To fully answer the question of which poster features and layouts function most effectively, we need to employ naturalistic measurements of factors that are often extremely difficult to measure without disturbing the participants’ natural behavior, either because of technological or ethical constraints.

For example, a video recording of a poster session from multiple angles would give us a wealth of useful data about attendee foraging behaviors, but most academic Institutional Review Boards would balk at recording all session attendees without handing out consent forms at the door. Even when such data can be obtained (as is possible with corporate or internal poster sessions), coding a set of moment-by-moment behaviors for each one of hundreds of attendees across a one hour time span may be a daunting task even for a team of research assistants.

Finally, a number of environmental and contextual variables likely impact attendee behavior in a poster session; especially, cognitive overload. For example, your browsing strategy may be different in a room containing 1000 posters versus a room containing only 6 posters. For this reason, naturalistic field studies of poster sessions are crucially important, despite their difficulty. Here, we have tried to summarize our initial efforts to capture some data about posters from attendees and presenters operating under the pressures of live, crowded poster sessions. But much more work needs to be done to measure poster outcomes in the field.

Future directions¶

The second, “#betterposter Generation 2” video on billboard posters, which introduced new layouts and concepts that should be tested.

We are at the very beginning of the quest to improve the effectiveness of scientific posters. Since these studies were conducted, new billboard-style designs and principles have been released (see Figure 11 and Morrison, 2020)[1] that incorporate many of the improvements suggested by participants in our studies (namely, greater emphasis on data and methods in addition to the key findings). Further, many researchers choose to incorporate idiosyncratic aspects of the billboard-style approach into their posters, either by creating their own layouts entirely or by simply making a key figure much bigger. While all this is promising, it makes measuring and comparing posters that much more difficult. For this reason, we think that measurement itself is the most promising area for innovation in poster research. Mobile eye trackers and ‘people counter’ technologies (used to track customer traffic in retail stores) may be of some use for measuring behavior in poster sessions, but they are often prohibitively expensive on an academic budget. We encourage researchers to find new and creative ways to measure factors like eye gazes, attention, and attendee walking paths in mass across big, live, crowded poster sessions.

Figure 11:Example of new, Generation 2 billboard-style layouts from Morrison (2020) that incorporate more data and methods, but remain to be tested.

Moreover, additional work is needed to move past imprecise distinctions between poster types (e.g., IMRAD vs. billboard-style). In lieu, controlled studies are needed to explore the impact of granular design features on learning outcomes. By focusing on design components on a poster instead its overall layout, research can begin to explore the differential impact of individual features on learning in scientific conferences.

Supplemental Table 1

Qualitative Response Codebook

Note. Open-ended questions:

- What are the strengths of the alternative poster template?

- What can be improved for alternative poster template?

- General comments about the alternative poster template:

Qualitative responses were broken down into individual recording units containing an evaluation (positive, negative, or neutral) and an object (target of evaluation). For example, a response of “I like the templates and key takeaways” would be broken down into “I like the templates” and “I like the key takeaways.” Codebook was developed using the constant comparative method. In this method, units assigned to a coding category are systematically compared to unit already assigned to that category, and these categories are integrated and organized through interpretative memos. The codebook was discussed with all authors.

| Code Name | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Irrelevant Information | Qualitative response was not relevant to the #betterposter. Provided response may have been explanatory information that was non-evaluative or indiscernible as to its purpose | The online version should have all the details |

| Presenter/Conference Feedback | Qualitative response was not actually related to #betterposter. Responses provided feedback for the conference organizers or for presenters but were not related to the #betterposter. Or responses provided feedback that were characteristic of all posters, but not the betterposter (e.g., posters used too many acronyms). | Presenters should stand by their posters; the poster session was well-organized |

| Experience of the audience member | These codes refer to the experience of the audience member. It focuses on what the audience member saw, felt, etc. It does not focus on the specifics of the poster design (e.g., what is on the paper). Instead, it is focused on the audience members’ reactions to what is on the poster. | |

| Generic positive | Related to the better poster, but not specific. Generic, overall evaluations of like of the #betterposter | I like it, innovative, good, etc. |

| Easy to consume - Positive | The information on the betterposter was easy to consume. This focuses less on the design elements (e.g., I liked the hero area), and more on the ease of use (the experience). It was easy to see, easy to use, easy to understand | Easy to read, easy to use, straightforward, clear |

| Fast to consume - Positive | The information on the betterposter was fast to consume. Focuses on the speed of information consumption and use of the betterposter within the presentation environment | Quick, fast, strategic |

| Poster Creation - Positive | The creation of the better poster was a good experience. Focuses on any aspect related to the creation of the betterposter from the presenter’s point of view | Easier to prepare, easier to create, useful to make |

| Visually attractive - Positive | The better poster is visually attractive poster design. Focuses on overall reactions to the visual presentation of the betterposter. Does not refer to specific features of what is on the paper (e.g., I liked the hero area), but overall reactions to the poster | Attractive, eye-catching, appealing, great visual, great design |

| Misc. Experience - Negative | The better poster provided a negative experience for the audience member. Broad “catch-all” category for negative experiential reactions to the betterposter. Does not include attitude evaluations towards specific attributes of what was on the paper (e.g., I did not like the hero area), but negative and idiosyncratic general reactions to the betterposter | I like to save posters and refer/review them later. the traditional poster is better for this |

| Poster Design | These codes refer to the actual poster design - what is on the paper. | |

| Central message- Positive | Respondent expressed approval for the main hero area. This is less focused on the experience (the better poster was easy to understand) and focused on the specific design element on the hero area. Respondents do not need to refer to the hero area by name but should clearly be referring to the central “main takeaways” section of the poster design | Like the key takeaways are highlighted, like the focus on the main findings. |

| Missing information - Negative | Respondents indicate that more information is needed on the poster design. Respondents indicate that not enough information was provided in certain or all areas of the poster design. Additional information would have been helpful, they would have liked more information on a certain aspect | Hard to understand context of the study without information, wanted more information on methods, difficulty finding enough information |

| Simpler design - Positive | Respondent likes the simpler design. Positive valenced statements referring to the simplicity of design or reduced amount of content on the poster | Likes that there are less words, that it is easier to find information, that there is negative space |

| Design isn’t simple enough - Negative | Respondent indicates that the design is not simple enough. Respondents indicate that there was still too much text or content on the design, respondents indicate a desire for less information or more simplicity | Posters should be less wordy, have less content, be more simple |

| Hero area - Negative | Respondents did not like the layout specifically of the hero area. Respondents provide negatively valenced feedback specifically about the hero area of the poster. Respondents do not need to refer to the hero area by name but should be clearly referring to the layout of the central message or main takeaway section of the poster | The title space was too big, there was too much unused space, the middle space was too big/variable |

| QR Code - Negative | Respondents did not like the QR Codes. Negatively valenced statements referring to the QR code or the information presented online through the QR code. Any quotes indicating an online poster were assumed to refer to the QR code experience | Don’t have QR codes, online poster didn’t have enough information. |

| QR Code - Positive | Respondents liked the QR code. Positively valenced statements referring to the QR code or the information presented online through the QR code. Any quotes indicating an online poster were assumed to refer to the QR code experience. information or provide a virtual poster | I like the QR code, information presented in the QR code was useful |

| More data visualization - Negative | Respondents indicate that more visuals are needed on the #betterposter. More figures or graphs or visuals should be encouraged. | Needs more visuals, needs more figures, should have a central figure |

| Colors/Fonts – Negative | Respondents indicate that they don’t like / want more fonts/colors. Feedback can be valanced in any way. | Colors and/or fonts are not visually appealing, should have more |

| Templates - Positive | Respondents provide positively valanced feedback on the templates | Templates were helpful |

| Templates- Negative | Respondents provide negatively valanced feedback on the templates | [Need] More diverse templates |

| Misc. poster features - Negative | Feedback is idiosyncratic or applicable to all posters. | Posters had too many acronyms |

The Authors would like to thank the CDC for contributing to the creation of this article by donating some of its employees’ valuable time._ _The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Copyright © 2025 Oronje et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

Sometimes, you need to explain a point

The second, “#betterposter Generation 2” video on billboard posters, which introduced new layouts and concepts that should be tested.

- IMRAD

- Intro Methods Results Discussion - Our term for the traditional Scientific Poster.

- Hess, G. R., & Brooks, E. N. (1998). The Class Poster Conference as a Teaching Tool. Journal of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Education, 27(1), 155–158. 10.2134/jnrlse.1998.0155

- Lingard, L., & Haber, R. J. (1999). Teaching and learning communication in medicine: a rhetorical approach. Academic Medicine, 74(5), 507–510. 10.1097/00001888-199905000-00015

- Ilic, D., & Rowe, N. (2013). What is the evidence that poster presentations are effective in promoting knowledge transfer? A state of the art review. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 30(1), 4–12. 10.1111/hir.12015

- Maugh, T. H. (1974). Poster Sessions: A New Look at Scientific Meetings. Science, 184(4144), 1361–1361. 10.1126/science.184.4144.1361

- Rowe, N. (2017). Tracing the ‘grey literature’ of poster presentations: a mapping review. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 34(2), 106–124. 10.1111/hir.12177

- Rowe, N., & Ilic, D. (2015). Rethinking poster presentations at large‐scale scientific meetings – is it time for the format to evolve? The FEBS Journal, 282(19), 3661–3668. 10.1111/febs.13383

- Dubois, B. L. (1985). Poster sessions at biomedical meetings: Design and presentation. The ESP Journal, 4(1), 37–48. 10.1016/0272-2380(85)90005-8

- Saffran, M. (1987). The poster and other forms of scientific communication. Biochemical Education, 15(1), 28–30. 10.1016/0307-4412(87)90143-9

- Pirolli, P., & Card, S. (1999). Information foraging. Psychological Review, 106(4), 643–675. 10.1037/0033-295x.106.4.643

- Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine Ways to Reduce Cognitive Load in Multimedia Learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43–52. 10.1207/s15326985ep3801_6

- Valois, P., Desharnais, R., & Godin, G. (1988). A comparison of the Fishbein and Ajzen and the Triandis attitudinal models for the prediction of exercise intention and behavior. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 11(5), 459–472. 10.1007/bf00844839

- Lam, H. (2008). A Framework of Interaction Costs in Information Visualization. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 14(6), 1149–1156. 10.1109/tvcg.2008.109

- Wegner, D. M. (1987). Transactive Memory: A Contemporary Analysis of the Group Mind. In Theories of Group Behavior (pp. 185–208). Springer New York. 10.1007/978-1-4612-4634-3_9

- Lane, J. N., Ganguli, I., Gaule, P., Guinan, E., & Lakhani, K. R. (2020). Engineering serendipity: When does knowledge sharing lead to knowledge production? Strategic Management Journal, 42(6), 1215–1244. 10.1002/smj.3256

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687